PHILIP GUSTON TALKS

The best way that I can think to honor and thank Philip Guston is to get people together and consider his work. Talks last 90 minutes in length and follow a chronological survey structure. We look at slides of Guston's work, explore his personal history and consider context. We focus on the artist's own ideas of his work, using rarely-seen footage of Guston working and talking. I'm a drummer focused on a painter and an artist talking about another artist: my own creative pursuit of Guston allows us to talk about artistic aspiration and keeping our heroes close, two lines of inquiry that will resonate for attendees reflecting on their own work and working lives.

These talks are for anyone and everyone, regardless of previous art experience or educational background, and they are designed to make attendees feel comfortable and respected and included. In addition to catalyzing community, sharing ideas, and considering the life and work of a truly great artist, my goal is that all attendees will find some inspiration, some enjoyment, and new ways of thinking about creativity, art, and their work, whatever that work may be.

PAST TALKS

2015

Nov 18 - Portland State University, presented by Time Arts Students (review article in PSU newspaper)

Aug 24 - Hollywood Theatre, co-presented with PMOMA (sold-out lecture, 140 attendees)

2014

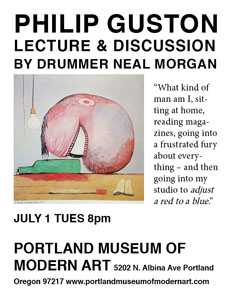

July 1 - Portland Museum of Modern Art (PMOMA), Portland OR

2013

Guston Centennial Tour:

June 6 - Extracto Coffee, Portland OR

June 9 - Stumptown Coffee, Portland OR

June 16 - In The Kitchen, Nevada City CA

June 23 - Gravel & Gold, San Francisco, CA

2012

June 27 - outside TIGA bar, Portland OR on a blanket on Guston's birthday

WHY PHILIP GUSTON

I had just turned 24 when the Philip Guston Retrospective exhibition opened at SFMOMA on June 28, 2003. I popped into the galleries on my lunch break one day and found myself surrounded by a dozen canvasses from around 1970, the year of Guston's landmark Marlborough Gallery show. The thick black lines and gorgeous buttery reds and pinks and ugly-smeared-white oil paints. The cartoon-like hooded figures smoking cigs and out for a drive through what his daughter Musa Mayer - in her wonderful memoir Night Studio - called "loony wastelands" of urban decay. Broken bottles and trashcan lids. Severed legs. Bricks, 2x4 clubs, whips.

I stood in that gallery looking, looking . . . and then the room sang. Years later I'd read about how a young Guston had felt that paintings by de Chirico made him feel as though he'd "come home". Something similar happened to me.

After some time, I read the exhibition’s educational material and came across the quote that sealed the deal; leading me irreversibly and forever into that late work. We had invaded Iraq a few months before the show opened. As we collectively and individually in whatever ways struggled through the darkness of the Bush Years and war and bigotry and greed in America - nothing new except that I was now adult-enough to feel myself in it - I felt like I was flailing in 2003, trying to figure out where I was headed as an artist and as a part of it all. Guston said this about the conditions that led to the body of work shown at Marlborough in 1970:

“When the 60s came along I was feeling split. Schizophrenic. The war, what was happening in America, the brutality of the world. What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated fury about everything – and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue."

Since then, I've been on a journey to see, enjoy, draw from, and understand Guston's work. It's been about creative aspiration more than anything; it's no stretch to say that what I do as a drummer has been informed more by Guston and his later canvases in particular than by any other art or artist. I'm drawn to and draw on, for example, by the harmonic co-existence of forces in the late canvasses. The ugly and the beautiful. The messy and tightly-composed. Humor and disgust and anger. Wrongdoing and forgiveness. Shame and acceptance. Mastery and slop. But it's also been about creating an artist hero for myself, a figure with the capacity to buoy, fortify, and challenge me as I've made my way.

ABOUT GUSTON, VERY BRIEFLY

Philip Guston (born June 27, 1913 and died in June 7, 1980), one of the leaders of the so-called New York School of American artists along with Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Franz Kline and others, rose to prominence in the 1940s and 50s with large “abstract impressionist” canvases. But as a young man, before his move to New York and name change (born Philip Goldstein), he executed figurative politically charged paintings that took on bigotry, war, racism, and fascism. Early drawings and paintings from the 20s and 30s included harrowing depictions of the Ku Klux Klan, the plight of the urban African-American, the terrible case of the Scottsboro Boys; his most important murals were pro-communist and anti-fascist.

In the late 50s and into the early 60s, forms began to fight out of the those all-over abstractions until 1965, when the artist, who was "sick of the art world" and at a crossroads in his work and personal life, stopped painting and retreated to his home and studio in Woodstock. A "tug of war" ensued in his work for over two years between "representational" and abstract paintings and drawings. In 1968, awakened by the Viet Nam War, the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bobby Kennedy and the police riot and unrest during the Democratic National Convention, he asked the question: “What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated fury about everything – and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue.”

Over the next two years, Guston worked at a blistering pace on new, representational, allegorical, figurative drawings and paintings that would be unveiled at the landmark Marlborough Gallery exhibition October of 1970. The works were harrowing, unflinching, and beautiful. Blood, broken bottles, severed legs, figures donning KKK-like hoods smoking and riding around in cars through bleak urban scenes. Guston had created an entirely new visual world in the late canvasses, using allegorical shapes and figures drawn largely from his early life, and executed in ways that showed a lifetime of studying Renaissance painting and expert referential use of Krazy Kat and other beloved comics' compositional and stylistic language. The art world, and some close friends, turned on Guston. His rejection of abstraction (he said in 1969 “every time I see an abstract painting now I smell mink coats”) and work in allegory and a “comic” style was correctly taken as a rebuff of the claims of purity and of “finding the sublime through art and art-making” that had buoyed an entire American movement. The master painter Guston had been reunited with the social and political imperatives and impulses that had driven him as a politically-courageous young man and artist. This resulted in his most important body of work from about 1968 to 1975 – and some of the most daring and influential American painting of the 20th century – and an incredible volume of increasingly revealing introspective work right up to his death in 1980.

For more information about Philip Guston, I recommend reading his daughter Musa Mayer's memoir Night Studio, his friend Ross Feld's Guston In Time, and Philip Guston: Collected Writings, Lectures, and Conversations, edited by his friend Clark Coolidge.